This week, ‘90s inspired first person shooter Project Warlock comes to consoles for the first time. Two years on from its PC debut, designer David Korzekwa talks to N For Nerds about working on an indie title, the timelessness of stylised games, and standing on the shoulders of FPS giants to put a fresh spin on a classic genre.

LG: We’re are just days away from Project Warlock launching on consoles, how are you feeling right now?

DK: It’s pretty nice, I only knew about it the moment the trailers came out. It was a surprise, I didn’t think it would be possible, this game was not very well optimised, so I guess Jakub [Cisło, Developer for Project Warlock] had to find some other team that would optimise the game for consoles, especially for Switch.

LG: Can you talk about how you got involved in the project – you were only the second person to come on board Project Warlock, right?

DK: Jakub was working on the game for about a year, developing the prototype and from what I remember, I stumbled upon it somewhere on Steam [Greenlight]. I thought to myself, I always wanted to make visuals for a game like this, so I contacted him and said I would really like to make this game look good […] It was a simple game and it looks like it works, and I thought to myself, let’s give it a try!

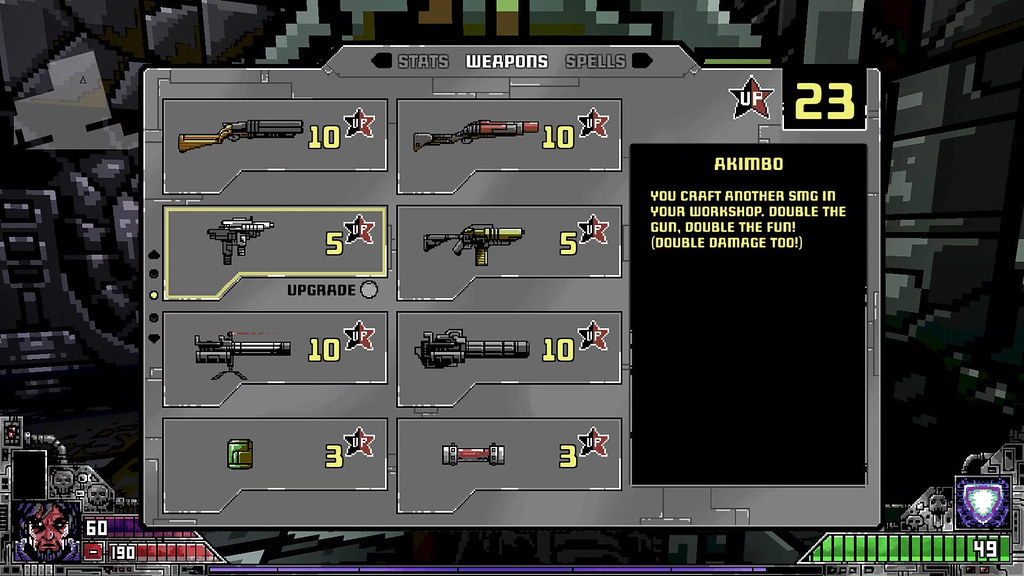

DK (Continued):Jakub was hesitant at first as he didn’t feel that he would be able to afford graphics and visuals, I said you know I want to do this for fun and if this game makes money we can share profits on whatever. So I did some basic graphics for the weapons, enemies, some textures, sent it to him, he implemented into his demo and we saw that it actually looked pretty good so we started working on it. After some time, it looked good enough, Jakub was actually starting to look for actual developers and actual funding for the game so I think this was the main reason why the game got created and why it was as good as it was, even though it was not perfect but given that we were not very experienced and this was our first game and we had huge limitations because he was developing the game in Germany, I was in Poland and other members of the team were spread around the world and we didn’t even have version control. So I was making visuals and sending them to Jakub, our friend was making level designs on a piece of paper and sending them to Jakub, the sound designer was making designs, sending them to Jakub and the music guy was doing music and sending it to Jakub and he had to piece it all together.

LG: So it was a real DIY effort then?

DK: Yeah we had to figure out a lot of things on our own […] sub optimal is the perfect word but it was still a lot of fun working on it. I always wanted to do visuals and animations for a game like this so because my day job was doing animations for interactive advertisements so it’s what I do but it wasn’t what I really want to do so I was trying to get into the business of making games. This was always my thing and this was always Jakub’s thing so we shared a vision about the game. We wanted to make something simple, something fun, something not too complicated for the first game. We went a bit overboard in some instances of the game, some elements of it but it’s normal when you’re first time making a game. You won’t be able to perfectly balance everything, you will make mistakes and you will need to learn a lot of things and a lot of it will be hindsight.

LG: Was there much of a brief set for the kind of style that Jakub wanted to go for?

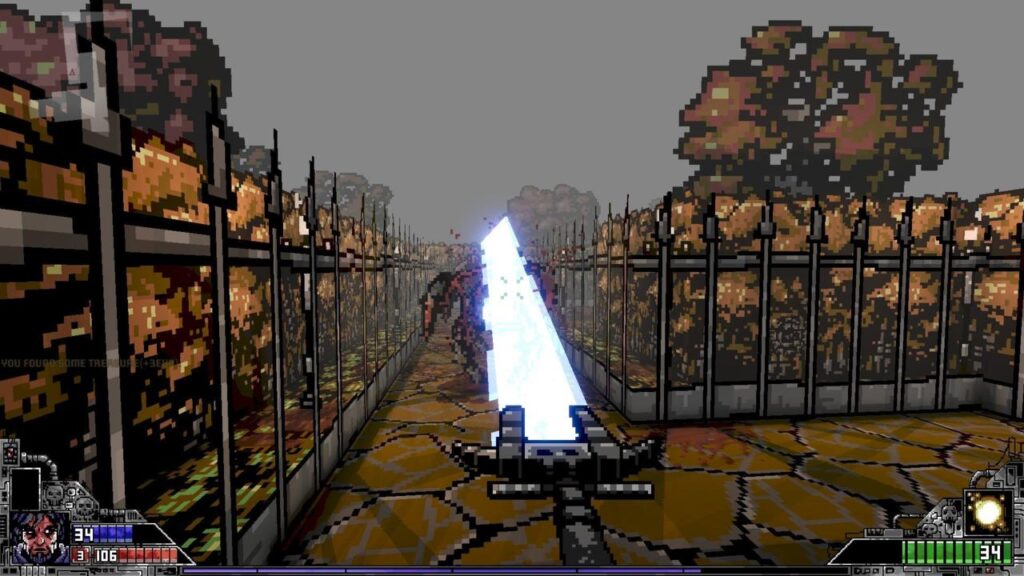

DK: Well the style had to be pretty simple because when you make a simple game the visuals have to be pretty simple so they go well together. I had an idea to use an 8-bit colour palette from the Commodore 64. It’s a very specific palette, it only has 16 colours and I thought I’ll make all of the visuals using only those 16 colours for the main textures, main sprites and effects. Of course, the game renders much more colours in the actual game because there is a lot of lighting, shading, etc. And of course the pixel art style, it’s something that works for simple games, it’s fairly efficient if you know how to do it right and can look very good if you figure out how to make it work in a 3D space. It’s not always easy.

LG: So even with a simple colour palette, it sounds like that comes with its own unique challenges in trying to actually make that work for these 3D environments.

DK: It works best when the environments are fairly simple, low poly geometry with a low resolution style because the more detail you start putting into it, the more you start to see the imperfections. So the mistake many indie devs make is they try to make the game as detailed as possible, high-res textures, HD textures, and because they very often make very simple games it starts to look like puppets on a string when everything starts moving around, and when they add physics to it, it can look very silly. So along with Jakub, we knew we needed to start small and the experience we get from this game we can use maybe in another game in the future […] we will be able to develop the skills and learn the tools needed to actually work on something more sophisticated later on.

DK (Continued): So we made a good call that we tried to keep it simple wherever possible. Of course, in development there is always this push to try to make the game the best thing possible and you have to control yourself and you have to constantly remind yourself, okay we might not be able to do this. Many times we had to back down from some ideas. Implementing systems and mechanics into a game, it’s fairly easy but testing the game, play testing involves replaying the game from start to finish, each time something changes and that’s something you need to always remind yourself.

LG: I guess you’ve got to really rein yourself in especially when it’s your first project and you really want make your mark, you maybe can’t be as ambitious as you would have liked to, especially with limited resources.

DK: Yeah, it’s like when you’re a coder you want to show your coding skills, maybe when you’re a musician or a sound designer it’s not a problem because you can make the best sounds and music and it will be just implemented but when it comes to visuals and systems, the more complex it gets, the harder it is in future to play test it to search for bugs and all the broken stuff. You might not be able to pick up everything because there is so much of it and with graphics you have to set some artificial limitations on yourself in order to keep in style and everything in the same style to be consistent but that is the thing when you start working, after a few months of work you notice you are getting better, you’re doing better animations, better textures and you look at your previous stuff and think I’d really like to redo this previous stuff and I think half of the textures, monsters, animations, weapons, I had to redo from scratch because I thought to myself, I can do this better.

LG: It’s two years down the line now from when the game first came out – do you still look at it now and think “oh I wish I’d done that a little differently”?

DK: Naturally. We’d both look at the game, especially when Jakub was learning specific coding skills for his job and he saw certain things he could’ve done differently, better optimisation for example. And I’d see the same things, I could do better, more efficient visuals, because this was the very first time I even tried to make pixel art visuals. If we started making project warlock today, it would be a very different game I’m sure because you always improve when you do something, learn new stuff and it’s natural, the stuff you do previously won’t be as good as your next thing but it’s the only way to learn, to actually do this stuff.

LG: Project Warlock has of course drawn comparisons to the likes of Doom, Wolfenstein 3D, are those the sorts of games that inspired you?

DK: We wear our inspirations on our sleeve. Maybe we were even a bit too open about our inspirations because people started to assume that we were going to make a game on the level of those titles like Quake or Doom and this was not physically possible because we were such newbies, we were just trying to figure out things. So we started calling our game “Wolfenstein clone,” to keep people’s expectations on what the game would be.

It’s a bit more sophisticated than Wolfenstein but […] okay, this is a good start, let’s make a good Wolfenstein clone, we can improve on some things, we can add some things to make it our own but let’s not compare it to Quake. Not yet, maybe in the future we’ll be working on something together, this would be on another level but now we need to figure out the basics and just ship a finished game which is better than a highly ambitious title that’s stuck in development hell forever. So this is a thing that I really appreciate in Jakub, that he was able to work on this thing until the end, put this all together and finish the job because it’s not easy and I know myself, in my life, I struggled in the past to work on a thing until the end because you have to be dedicated and you have to really enjoy what you do. Because it’s not easy to find people that you enjoy working with and that are willing to work through the problems, work through difficulties and just get things done.

LG: There are a lot of people looking forward to this game and it received good reviews already – do you feel a renewed sense of nerves now that it’s going out to a new audience?

DK: Of course there are people who will look at our game and think “wow that looks interesting”, that’s awesome, that’s why we didn’t try to make this game too hardcore and too inaccessible, […] you can’t make a game for everybody, you can do, for example, difficulty levels and try to ensure that everybody will be able to have a chance at it but we also wanted to make the games that we ourselves would like to play and people who like these kinds of games.

DK (Continued): The concept has to be simple, it has to have good controls, good levels, good gameplay and have to be refined enough for people to enjoy it, to appreciate it, so you don’t have to constantly remind yourself that yeah it was a small team of noobs, what do you expect from this game! […] Because people always want to compare this game to Quake to Duke Nukem and people didn’t realise that these games, even if they were made 20 years ago, they were made by professionals with big budgets and technology and experience so yeah, even to match the quality of Doom or Duke Nukem you have to know what you’re doing already and have several years of experience even if you’re working on an indie title, even if you’re working on a shoe string budget.

LG: Didn’t John Romero himself actually comment on the game and say that he think it looked really cool?

DK: Yeah, it’s something that you don’t experience every day when you are a nobody developer making your first simple game and somebody you know about, you’ve admired, played his games and he’s commenting on your game, it’s like “I’m not exactly sure how to react to this! How should I feel about it?” […] Our game is getting some recognition, okay let’s not allow this to get into our heads, let’s just go back to work, enjoy this but let’s go back to work and don’t let all these people be disappointed when the game actually arrives. It was really cool, a really nice feeling.

LG: We’re nearing the end of a console generation and entering a new one, what kind of future do you think this kind of retro style of gaming has?

DK: I think we are living in the best time for these kinds of games. One of the reasons we did the game in a style like this is because it’s timeless, it’s not the best quality pixel art, not the best quality animations, not the best quality texturing level design but as a whole, it looks good. And it will always look as good as it looks today because it’s not chasing the cutting edge [..] it doesn’t have to be cutting edge because it doesn’t have to be realistic, it’s stylised and stylised games are like Disney animated classic movies, they look great when they came out and they will always look great no matter how the technology develops. This is why the games from the ’90s look absolutely wonderful, even today. Quake, absolutely wonderful, it could come out today as an indie title and it would look great because it’s artistically consistent and everything, the textures and the models look very well together.

Duke Nukem, Blood, all these games, very stylised, they aged very well because although they were the cutting edge at the time they were very first introduced, they didn’t aim for realism. Once games started to embrace 3D they lost something and most of them have aged really badly. Your ‘Solider of Fortune’s your ‘Turok’s, your ‘Rainbow Six’s, you try to play these games today, they might be fun to play but they don’t look as good, they won’t inspire you the way the Duke Nukem or Quake or even Doom can inspire you even today. So I am very glad because for a very long time, people stopped making those classic stylised shooters, they stopped making platform games, they stopped making isometric games because they all were following the trend of just pushing the visuals, pushing this to realism […] Now in this new era of indie games were AAA publishers have their own niche and independent developers have their own niche, they are able to make platform games again, stylised retro shooters again, isometric games again and I am very happy for that because the ’90s was personally my favourite era of video games.

LG: With Project Warlock, there’s a timelessness in that sort of straightforward gameplay there’s no complicated narrative, there’s a guy, with his guns, shooting demons – the game is more focused on fun. Has that been missing from more modern games do you think?

DK: I am all for there being all kinds of games, so I’m happy that there are ‘Bioshock’s, ‘Mass Effect’s, that there are games that are super realistic, that are cutting edge but I’m also happy that today we have the whole spectrum because this is what was missing from the industry for a pretty long time. There wasn’t Unity, there wasn’t Unreal Engine, there weren’t tools that would make game development accessible to regular people, there wasn’t funding platforms like Kickstarter, it was very different. People could say there is already too much of retro shooters now because people are jumping on the bandwagon and I say no there is not too much of these games because people who are working on them are also figuring out their formula.

LG: You talk about loving and appreciating those games from the ‘90s – do you hope that maybe in another 10 years’ time people look back on the game you’ve made and think the same thing?

DK: Yeah, it’s possible and it would be great, it’s nice to think about it. We are all standing on the shoulders of giants so everything we have experienced before has influenced us, even for the things that weren’t perfect because even those games we are being inspired by they were not perfect games. But it didn’t change the fact that they inspired people and inspired all the future games that addressed the problems of those previous pioneers. We were doing the same, we were trying learn from the games that were before, trying to figure out how it’s done and maybe someday we will be able to surpass not only our first game but these games from the past and make something that will not only inspire people but we will also make a game that will survive the test of time.

Well, that’s our Interview with David Korzekwa designer of “Project Warlock”. Project Warlock will be available on console from June 9th for PS4, June 11th for Nintendo Switch and June 12 for XboxOne. Let us know what you think in the comments below, don’t forget to follow us on Twitter, Facebook and subscribe to our YouTube channel and if you’re feeling generous feel free to donate to our Patreon, thanks for reading.